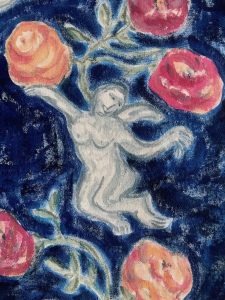

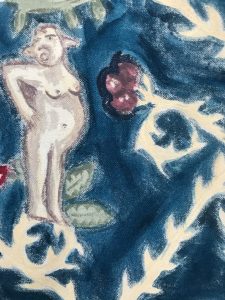

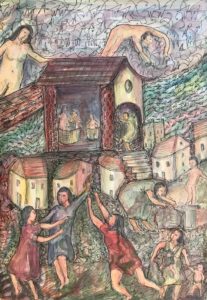

Paintings that explore women and visibility through pattern, myth and historical symbolism.

For women history is not made up of one victorious moment, it is made up of daily domestic minutiae and selfless caring acts. All art explores our system of values and these paintings mix multiple frames of reference creating a dialogue between: ancient myths and contemporary tales; historical pattern and contemporary Subjects; universal symbolism and persona.

Delpha Hudson is an artist based in Cornwall whose practice explores how female bodies act as a vehicle to empower, connect and deal with trauma. She is currently working with conceptual elements of narrative in representations of identity and women’s lived experience.

I never dared hope that I would have the opportunity to work on such a grand scale. I’ve always wanted to make history paintings about women’s lives and discover new ways to make them visible. History is not made from one victorious event, it is made up of daily minutae, and domestic detail.

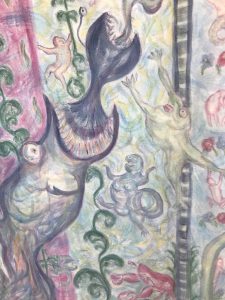

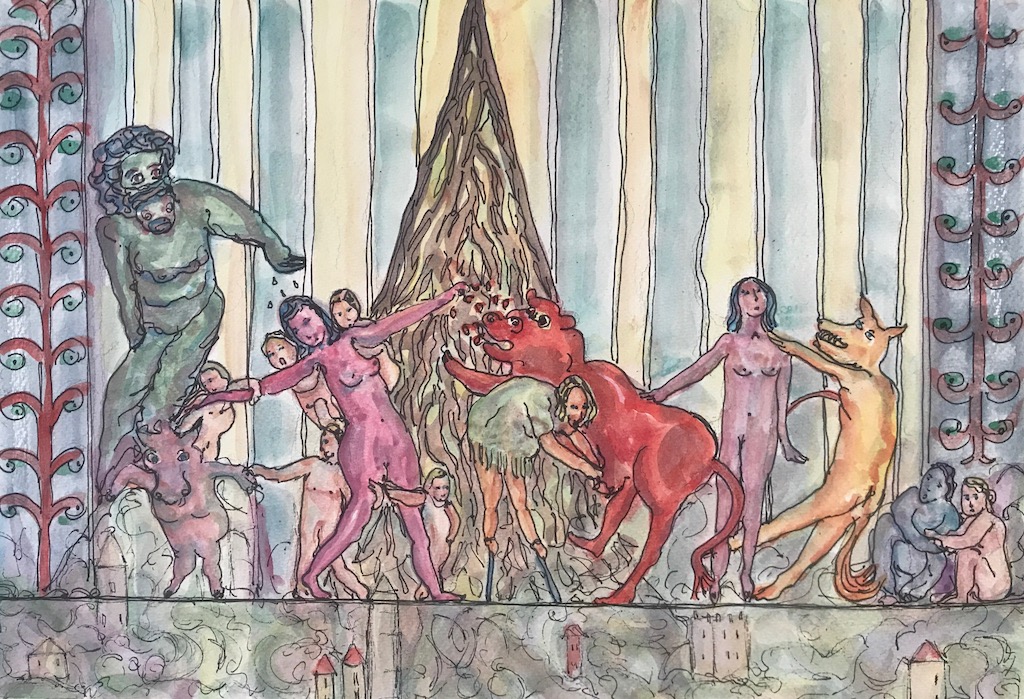

Carnivalesque in its scope and multiplicity of styles the painting explores how to create dialogue between ancient myths and contemporary tales; historical pattern and contemporary Subjects; symbolism and flights of imagination.

Bakhtin proposes that all art forms explore our system of values and that there can be no single voice. This frieze-like painting is a grand gesture, laced with socially charged intertextual references that celebrate the mundane and the invisible.

Delpha Hudson, October 2022

TWISTING THE FABRIC OF OUR EXISTENCE – writing on women, myth and monsters

Delpha Hudson, August 2022

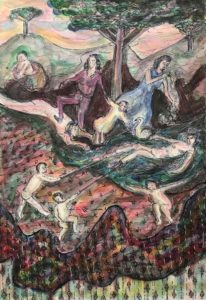

I am drawn to medieval patterns, symbolism and re-presentations that hint of ancient myths embedded within contemporary culture. Representations of women, myth and mothers explore contemporary concerns about visibility and gender equality.

Ancient stories and medieval bestiaries contain strange personifications that are often baffling and incomprehensible to us now, yet beneath our layers of rationality we are drawn to an archaic past. Exploring morphologies and meaning in myth is an interesting lens for underlying truths about human existence and gender politics – wherever you are in time.

In ancient history, apotropaic images of mermaids, sheela-na-gigs, chimeras, antiches, gargoyles were used to ward off evil; demonic figures yielded protection against demons. This is a strange and compelling contradiction in an epoch that promotes a ‘good versus evil’ by-line in all of its stories. It holds intriguing possibilities for multi-dimensional and differentiated representations of women.

Many contemporary women writers explore classical myths and stories with women-as-monsters (including Medusa, Medea, and Melusine), in order to re-write them, reveal deep psychological insights or destroy flattening stereotypes. These creations are hybrid, encapsulating curiosity and possibility to re-image a ‘natural’ order. Critical of stories that entrap women in webs of cultural inequality, they re-imagine ways that women might emerge from male-centred hierarchies. Like an apotropaic image, they are simultaneously satirical and contradictory, empowering and serve as a reminder of deep-rooted biases that we have all inherited.

Marina Warner warns of the problems of perpetuating old myths, ‘as this may ‘magnify female demons rather than lay them to rest…’ (i)

Warner’s body of work tackles myths both as stories, and lies. Re-writing and renewal is at the core of her life’s work. She is an influential proponent of putting myths to work in order to promote equality for women. Myths are endlessly renewable yet she advices caution as,

‘ironies, subversion, inversion, pastiche, masquerade… all buckle at the last resort under the weight of culpability the myth has entrenched’ (ii).

Her warning is accompanied by her deep commitment to re-interpreting myths about women and monsters. The creative appeal of the surreal, the unknown, and the metamorphic, as described in myth, is an intriguing way to represent women’s lived experience. They say, ‘we all love a good story,’ Warner adds: ‘every story must have a monster’. Her insightful representations of women are multi-dimensional despite and because of the contradictions.

As a theory, an aesthetic, and a medium, historically the Grotesque has been a creative, redemptive and transformative protest against oppressions. The Grotesque includes not just monsters but messy and disgusting things that relate to the primal experience of life. Grotesque combinations ‘thwart common tools for explaining things’ and these ‘distortions’ can be seen as ‘harbingers of cultural renewal’ (iii).

Women-monsters or monstrous women link to particularly troubling misogynist tropes. Women’s bodies have historically been considered Grotesque and monstrous – as anything that is not the ideal male ‘norm’. They are messy, open, penetrable, able to reproduce and to be multiple. Early humorous Grotesque drolleries, like the playful and satirical 1595 German text ‘A new disputation against women in which it is proved they are not human beings,’ mimicked widely shared and convenient beliefs that echoed the ancient Aquinian question: ‘do women have souls?’ (similar to medieval conundrum: ‘Do animals have souls?’ and the conflation of women with animals and lives stock as a matter of ownership). Evoking simultaneous laughter and anger, historical Grotesques are an uncomfortable recognition of residues that echo in contemporary misogyny.

Myths and monsters have a specific relation to the messy, reproductive and porous female body. Barbara Newman in her book about medieval thinking, re-defines porous as ‘permeable’* – not just a description of all that is ‘wrong’ with a women’s bodies but as a way of thinking about the Self. Permeable thinking in a pre-Cartesian age is an example of being connected to all forms of life; thinking of others, community and humanity. There is beautiful irony in past and present imagery of woman-as-monster, her ugly ‘permeability’ a useful appropriation, put to work in self-less, multiple, caring roles. Women’s bodies have been so often linked to nature – as beautiful and frightening, it is a powerful thought to envision a world where everyone is a woman-monster, transformed by our connection with the world and to all around us.

Bakhtin likened the Grotesque to an old pregnant hag, combining both disgust and impossibility (little did he know what the future held: cosmetic arrangements that remove the possibility of looking like a hag; scientific advances that enable women in the ‘hag’ category to have children). He used this example to show how the Grotesque is intentionally offensive, and may surprise us into thinking differently. Bakhtin’s ideas about the Carnivalesque* are equally surprising and include chaotic representations of equality yet the question is -do these extend to women. Suspicion and ambivalence are built into both the Carnivalesque and the Grotesque. So whilst suspiciously playing with the Grotesque ‘law of infinite metaphor’, I fear that infusions of old myths may act as a kind of ‘collusion.’ Nonetheless, I am also encouraged by tensions created between apotropaic potential and historical laughter is also be a ‘form of well-proven magic…[that] offer[s] a curse in order to command its field of meaning’. (iv)

The ‘well-proven magic’ of re-writing and reformulating ancient myths, fairy tales and wives tales is about change and renewal. From Disney’s new film ‘The princess’ to Zimmerman’s ‘Women & Monsters’ to Natalie Haynes feminist re-workings of Greek myth to a current exhibition by Mary Beard about feminine power and the demonic at the British Museum (to mention a mere few), the fruitful premise of mythic stories is their potential to disclose the truth about ourselves and our lives.

The hubris of myth, women and monsters are symbols for contemporary metamorphosis and change. Myths and symbols contain complex ambivalences and a heady exhilarating mix of beauty and strangeness. New and old creations counteract invisibilities and conjuring new myths, with multiple medievalesque figures. I aim to create an intrigue of contradictions about women, monsters and myth. Wherever we are in history, the re-telling twists our fabric of reality and is a precursor to change.

References:

(i)Marina Warner, Six myths of our Time, p 15

(ii)Marina Warner, Six myths of our Time, p 15

(iii)Ed james luther adams & Wilson yates. The grotesque in arts and literature,

(iv)Ed james luther adams & Wilson yates. The grotesque in arts and literature

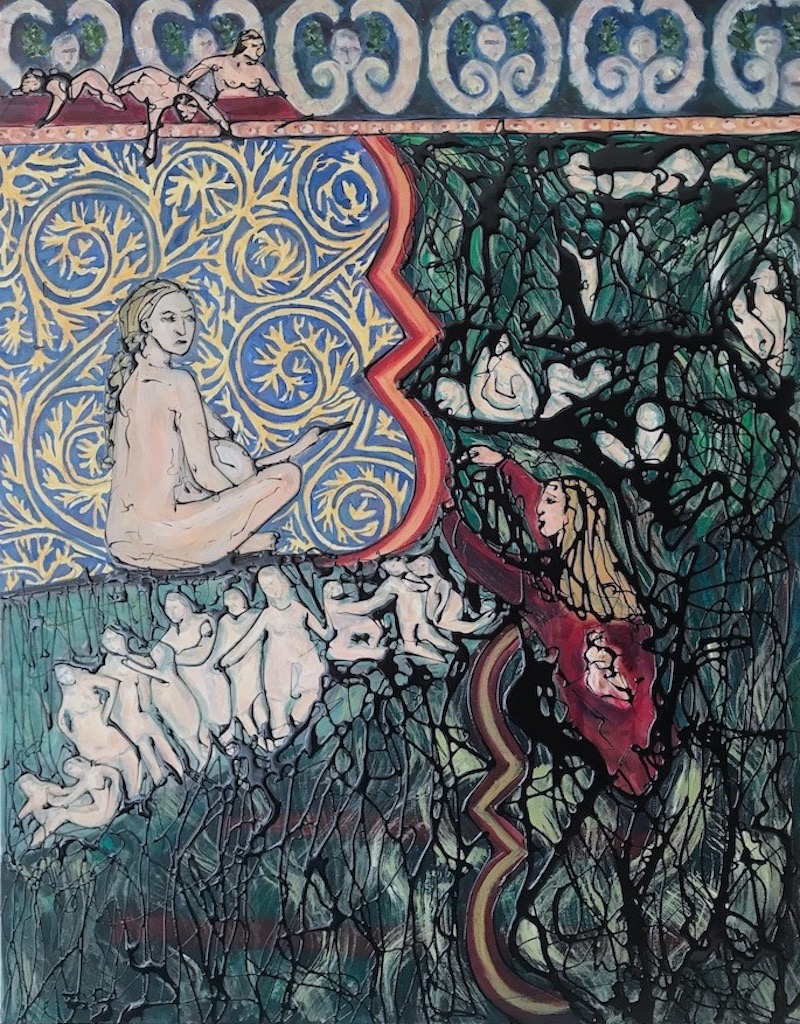

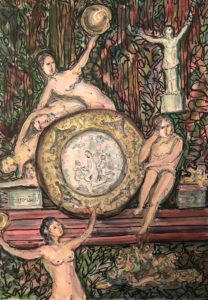

This painting explores transformation and the grotesque in relation to women and their life stories. Using grotesqueries within the patterns around the main figure.

There are also gargoyles within the formal arched composition with grotesque patterns around them. The grotesque as an art design style was based on the Roman art found in ‘caves’ under Pompeii in the late 16th century (hence grotesque from ‘grotto’ or cave). Over time the term ‘grotesque’ became a description for ugly, monstrous or surprising juxtapositions, that were often comical and satirical.

In writing about carnivals and the chaotic play of the masses mocking hierarchy and power, Bahktin developed the idea of what we now call the ‘carnivalesque’. Some of his ideas were based around the grotesque body, which he described as a potential for change and transformation. Writing of the female body which is monstrous in its ability to be ‘more than one’ (to reproduce, to have another body within it):

‘The grotesque body is a body in the act of becoming. It is never finished, never completed. It is continually built, created and builds and creates another body’

Bahkitin from ‘Rabelais and his world’

Indeed historically the woman’s body was considered monstrous. It was not the ‘norm’ (a male body) and with its reproductive capabilities and mysterious interior architecture little understood. We may laugh now at this evident ignorance but it is interesting to think about how arcane belief in women’s monstrous body (and how it might make the mind defective) structured cultural and philosophical thinking for hundreds of years. Wondering how this perception of women may still be affecting our attitudes today, thepainting really asks: ’ Are women still considered monstrous, and if so who made the monster?’

The project is of re-building the perception of women and their potential for multiplicity, not a single unitary Self but many. Christine Battersby’s philosophical metaphysical writing on women, individuality and the embodied self, move away from traditional systems of thought that are based on the typical human (man), expanding limited understandings of Self(hood) and allow us to think about patterns of potentiality, flexibility and flow: the ‘act of becoming’ (many things).

When a studio visitor, Davina Kirkpatrick, saw the figure in the painting said she looked as if ‘she were a silhoutette stepping out of herself’. The figure went through many transformations before ‘standing still’ in this painted form. I wrote about this at the time:

‘She surfaces breaking the flatness of the painting. I want to draw her out. She is ghostlike yet not formless. She carves spaces for things and frightens away evil spirits. Caught mid-motion, her gesture suggests she is potentially permeable, porous, shifting. The past is behind her. She laughs yet is serious, drolleries, grotesques and gargoyles surround her yet she escapes contradictions of domestication, monstrosity, care and invisibility.’

I wanted the figure to somehow evoke permeability and the potential for transformation. Permeable rocks let the water in, they do not have barriers so are pervious to their surrounding. Psychology names permeable personalities as a condition that allows a Self to be much affected by people and things around them. Permeable personalities are not impervious to their surroundings they are much affected by them. Barbara Newman writes about medieval society and in her book ‘The permeable Self’ she describes a very different relationship to Self and others during this period in time. She uses the term ‘permeability’ to communicate connectedness and responsibility to others, suggesting that we can only understand the past in terms of this belief; that other people were more important than individual choice and freedom. In connecting women to their potential to transform, to be ‘more than one’, always changing and also ‘permeably’ connected to others – including different parts of herself (or Selves) I am suggesting that women are more connected to others, more permeable, yet this should not mean that they are invisible.

Apotropaic images are powerful talisman, gargolyles and monster effigies were made to keep evil at bay. Creating beastiaries within patterns aims to balance beauty and horror, creating new satirical myths that reek of the domestic, yet aim to escape definitions of limitation, definition and identity. I like the idea of ‘monstrous’ women, the ambiguity and ambivalence in a culture that demands beauty. Women lead ambivalent lives, trying to be ‘good’ and beautiful, when of course they are often ‘bad’. Which ever way they are, they might be ghostlike, permeable, ugly, they are constantly fluid within the patterns and restraints around them. Representations of women should break free from past assumptions, patterns and invisibility and be seen.

Delpha Hudson, October 2024 This painting is currently on show at Tremenheere Gallery

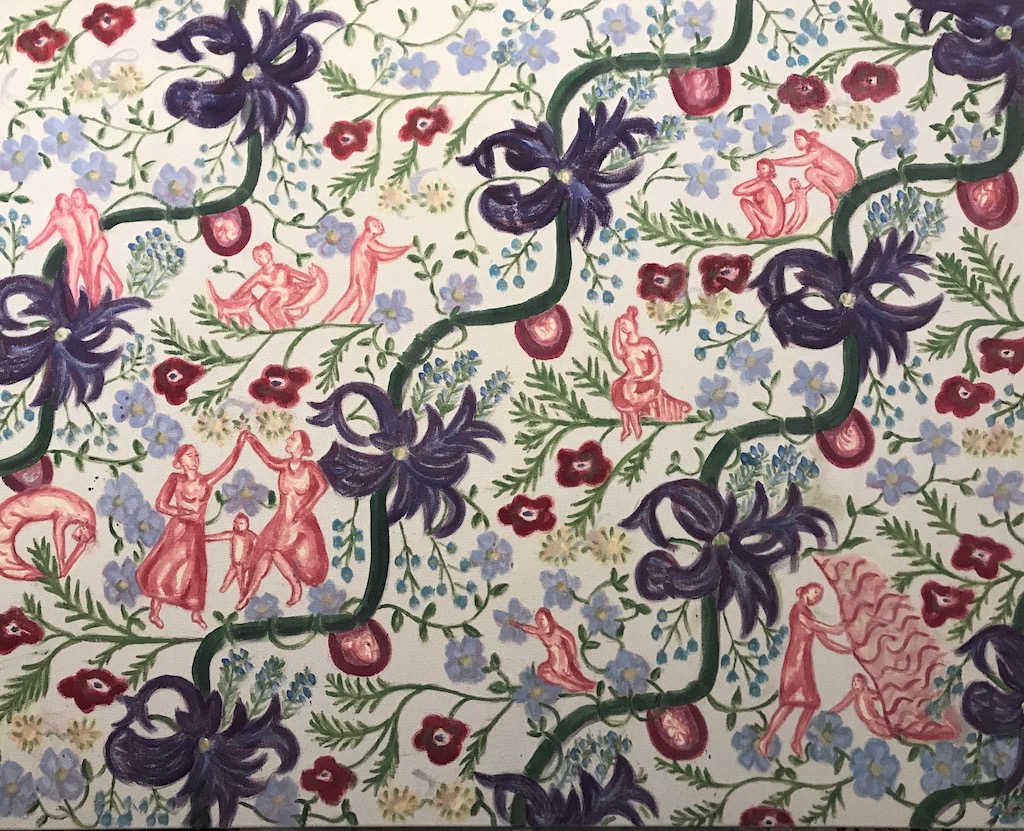

Some thoughts on a contemporary medievalesque

For some years I’ve been making figurative paintings that aim to evoke the human condition, especially the continued plight and inequality of women and carers, who are often the very lowest paid in society. Current paintings are fuelled by a dark fascination for medieval imagery, patterns, and symbolism. Is it just me, or is there a revival of interest in medieval imagery in contemporary painting? Artists constantly dip their toes in the lake of historical painting and with cyclical ‘returns’ (Hal Foster) to styles and historical art movements, perhaps this renewed interest is a natural ‘return’, or are there other reasons for this medieval zeitgeist?

Perhaps the medieval period (c. 500-1500) with its frequent recurrence of plagues seems closer to us and more resonant since the Pandemic. As the ‘danse macabre’ of life and death becomes reality, we are reminded of the equalising forces of death and mortality. Perhaps it simply makes us realize that we have so much more in common with the humanity of the past, than we thought.

Medieval societies were rule bound, patriarchal, unequal. Modern society prides itself on equality, yet Pandemic statistics reminded us of how much life expectancy is based on status and income. Seeing the medieval period as a mirror, it is natural to take another look at Bakhtin’s theories of medieval carnivalesque as an ironic equalising force.

Mikail Bakhtin’s writings about medieval folk cultures inspired philosophers from the 60s onwards (significantly Julia Kristeva). He proposed that carnivals and festivals brought together the most unlikely people. In addition to encouraging interactions between high and low born, carnivals united all in celebration, rather than condemnation and judgement. In the inside-out world of the carnival anything was possible. Eccentric behaviour could be revealed without consequence and Bakhtin proposed that a bi-product of inverting the usual societal divisions allowed a kind of grotesque realism that invoked laughter; laughter as a therapeutic and liberating force that degrades power relations.

The notion of the ‘carnivalesque’ is a potent force in allowing invisible and voiceless masses representation. It is a powerful idea that over the 20th and 21st centuries has influenced figurative painting as a social and political act (look at writing by Tim Hyman). I find this a very encouraging reason to make figurative paintings that brim with figures and bizarre medievaleque imagery – and to paint women into new historical frameworks.

Originally a student of history, I moved to Cornwall for many reasons, yet perhaps it is not a coincidence that I now live cheek by jowl with medieval imagery. I live next to a church with marvellous ancient carvings, including a carving of a merman. Less well known than the famous mermaid carving of Zennor, it is nice to know that for once that history favours a story about a woman.

Half-women, half-beast symbolism is a complex representation of duality and female metamorphic potential. Every culture has a version of these female deities, often carved with beautiful curving lines with other strange animals and symbols. Medieval society and the church often appropriated such symbols for a largely illiterate populace to expound ideas about a woman’s place. As Edwin Mullin explains,

‘There can only one origin of so pervasive a desire to control woman, abuse woman, to set her up to tear her down, enclose her in a labyrinth of moral strictures with so many blind exist she will never be free – and that is fear’.

Medieval symbolism is powerful and fearful. Every illuminated text, painting or tapestry is full of arcane references that seem hard to penetrate and understand and in strict male-dominated medieval societies, female symbols, like the mermaid, were constantly in flux, inherently contradictory – powerful, evil, and frightening.

‘Old as new’ is a renewal of meaning through appropriating and re-imaging familiar imagery. This is an old idea from Heraclitus law of enantiodromia (c. 500BC). He declared not only that old is new that eventually everything becomes its opposite. As ancient symbols morph and change, meanings and representation can be manipulated to promote new ways of looking at things.

Denigrating and debasing imagery of powerful female symbols (like mermaids) can be understood to be part of a timeless propaganda campaign that confined women’s power. Feminist artists of the 60s and 70s reinvested in old symbolism in order to create new iconographies, realising that symbols are a mould in which the meanings of male dominated culture are poured. As Griselda Pollock writes

‘the very signs and meanings of art in our cultures have to be ruptured and transformed because traditional iconography works against women’s attempts to represent themselves.’

The past is a mirror to observe our own times, and as we learn from what has gone before, it is a touchstone for the present. As a lens that enables us to look at things differently, it is the very contradiction of using medieval symbolism to promote visibility and equality for women now that appeals to my sense of humour. There is easy satire in raiding a medieval treasure chest for iconography and symbolism. Medieval art is deceptively simple. This simplicity is broken by swathes of dark humour and imagination (like that used in marginalia on the edges of manuscripts).

It is idyllic to think that the vast networks of symbolism for each animal, flower, tree or object, is an insight into a different world. Yet what is truly disturbing, is how little some things have changed. Medieval imagery is resonant and ripe, ready for playful carnivalesque humour in contemporary art that promotes equality and aims to be an agent of social change.

Delpha Hudson, January 2022

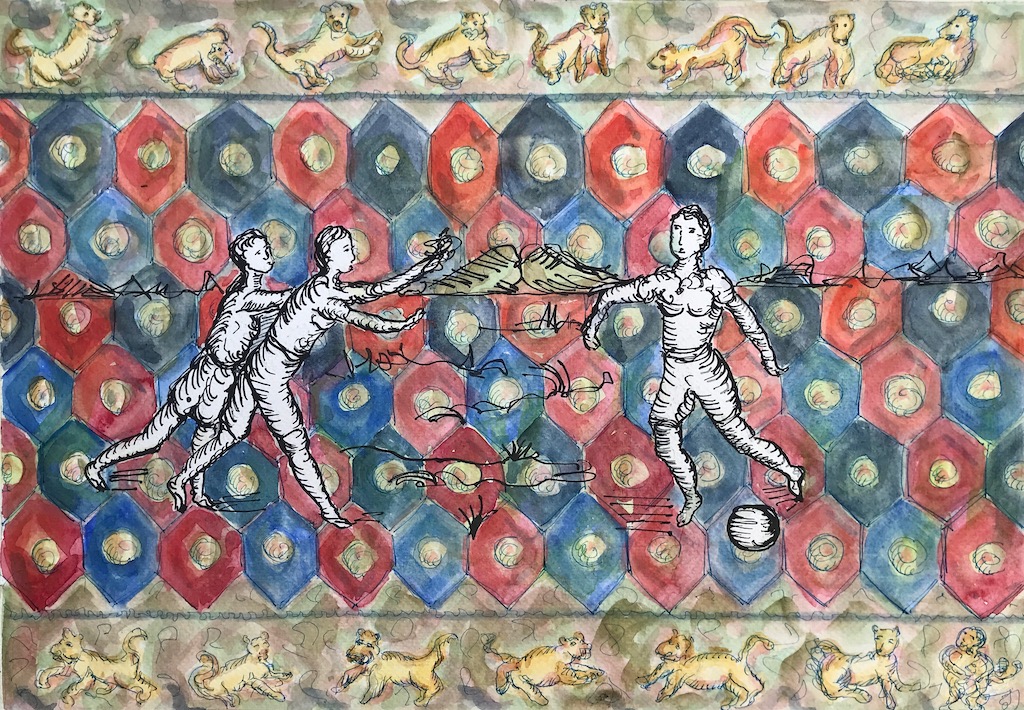

Notes on ‘Remember when life was so simple’:

Like many of my painting titles there is Intended irony in the title as life is never ‘simple’.

Continuing to work with a ‘contemporary medieval’ aesthetic this one is a little different because as an experimental preparation for the painting, I ‘wrote’ it first. Pre-describing visual content and feeling, before painting it was inspired by AS Byatt’s book ‘Portraits in Fiction’ and part of this painting is based on a rare self-portrait life-drawing made in 1997.

This is the ‘written painting’. How do words and image operate differently and over time?

‘There is a medievalised portrait of the artist. Based on a moment in time captured yet false. She is heavily pregnant and seems to calmly appraise and record herself, her body. It contradicts a memory of unreal time; illnesss, loneliness and poverty.

Behind her is a delicate historical pattern with fronds that entwine. Below her there is a tranche or line of figures that are queuing as if going to work or to a war camp.

A large brightly coloured parenthesis or bracket shape taken from an illuminated manuscript divides her from the rest of the painting frame. The medievalesque is also used in a motif at the top of the painting that uses a marginal pattern of faces. On the left there are comic figures that hang over a this pattern as if they are on a balustrade, like peeping Toms or voyeurs.

The other main figure is not based on a life-drawing, she is more naively drawn. She is looking up at the portrait of pregnancy with amusement. Her age is unclear. She has contemporary clothing of a red coat with a design of a small figure on the back. of her red coat. She is pegging out washing.

The washing is drifting in the breeze, acting as a reminder of domestic work but also intimating curtains and revelations in time. Behind the washing there are other figures of women and children who seem to be relaxing and playing yet there is something insubstantial and tense in their presence.

Shown at Penwith Gallery, St Ives, 2023

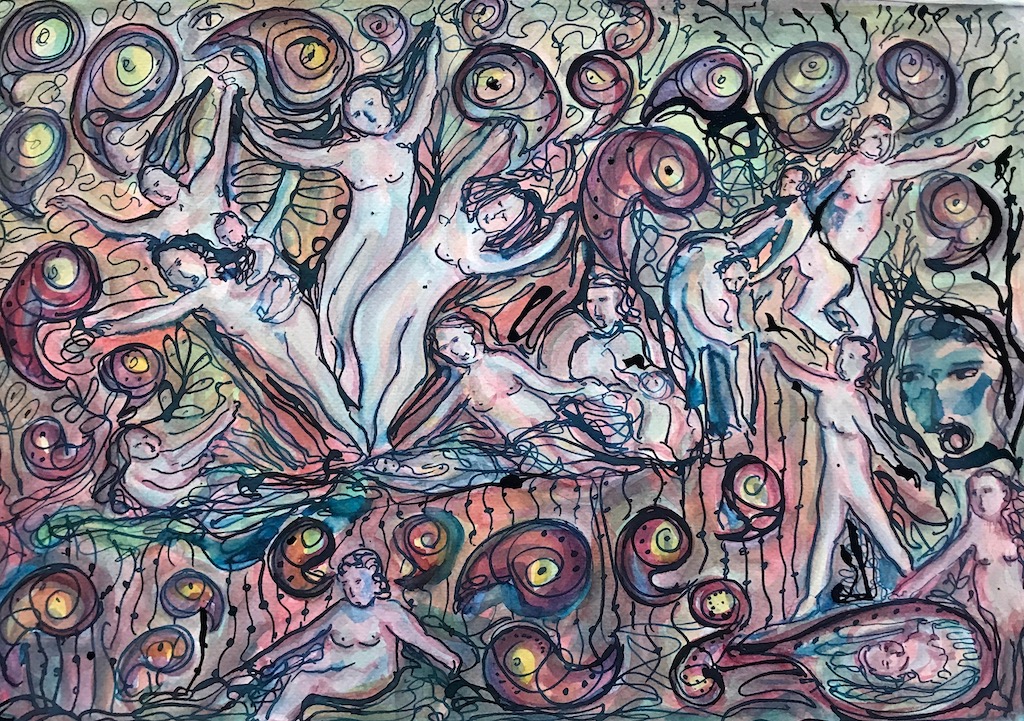

Notes on Remembering things that never happened, 2022

Strange metamorphic sea creatures invaded this painting that features broken windows, textiles and banners that have latin inscriptions: Libertas perfundit Omnia luce – freedom will flood everything with lightSola libertas –that I translate as ‘only liberty’.

What is liberty? What is choice? An ability to choose the ‘lesser of two evils’? But too much choice is as Habermas said bewildering and delimiting.Yet perhaps liberty and freedom come from limitation; a knowledge of the past; knowing what has gone before so that we know how we are limited and what choices are left to us.

The past engenders a liberty to choose our story – and maybe to choose the lesser of many evils.

Experimenting with inspiration from Marina Warner’s world of myth and ekphrasis, Delpha decided to write the story – or ‘mythic versioning’ of this painting:

The family on a tight rope (or carnival transformations of circadian myth) by Delpha Hudson, June 2022

The blue and yellow chintz curtains were firmly shut. Their very stolid solidity was safe and secure and she hoped would guard against intrusions of any kind.

They did not entirely black out the bright midsummer’s evening, yet she optimistically closed her eyes and invited sleep to whisk her consciousness away as softly as theatre curtains soughing across a stage.

In this she was not disappointed. She did sleep. The only rather irritating thing was, as we all do sometimes, she dreamt vividly that she was awake.

Far above the cities and town of a rather beautiful but perhaps bucolic Britannia was stretched a tight rope. Any excitement from the vertiginous effect of finding herself balanced on this gossamer thread was somewhat ruined by the crowd that she found herself sharing the tight rope with. Indeed were it not for a sudden sharp intake of breath as she looked down, she might have found enough lung capacity to shout at these creatures that were sharing her space, although calling the inch of rope ‘a space ‘was generous to say the least.

Ridiculously threatening any possibility of living space, she asked herself, who could they possibly be? None of these small children wrapped like anacondas around her torso were hers. Yet she felt entirely responsible for them. Fearful even. One of them was on the back of a warthog like creature, who in its friendly fashion was also letting one of the cling-on kids touch it.

She hardly dared look elsewhere or she might lose her balance and fall but from the corner of her eye she saw something ridiculously large, strange and lost on the warty creatures back. Green and slimy, she could feel something dripping like snot on her skin. Or it could be any one of the grasping children.

This made her realise with a shock that, in turn, she was also scattering something very generously into the open mouth of a she-cow. Now that can’t be right. Surely a cow is a she, so there should be no need to add ‘she’, yet there was something to entirely comically human about her. There was also a cow-girl on stilts milking her, so she wasn’t your average cow for sure.

Perhaps that might be a very useful thing, she thought, as the children will need feeding. She was then annoyed at herself. Just like her to be so practical. Why couldn’t she just change places on the high wire with the cow-girl on stilts. Or the naked girl who was resting her hand fondly on the red she-cow like an affectionate familiar friend? But she didn’t fancy the look of the yellow fanged creature. Perhaps that’s why the couple in the corner seemed to be cowering at a safe distance.

Certainly changing places with any of them seemed preferable to the sticky residue rippling off the amphibious thing behind, which was threatening to make the babies and children slither off. Of course, by now she wanted them to slide off, as she was getting very tired. Yet she decided, she would not make any sudden movement, she would stay still and do her bit – the best she could do in the circumstances – and hope not that she and her surrogate children would not be pulled in by the swirling mountain between the curtains.

Ah the curtains….

Some works on paper shown here are still available do get in touch or go to shop.

Other projects from 2022: Synesthesia & One+All a site specific performance project