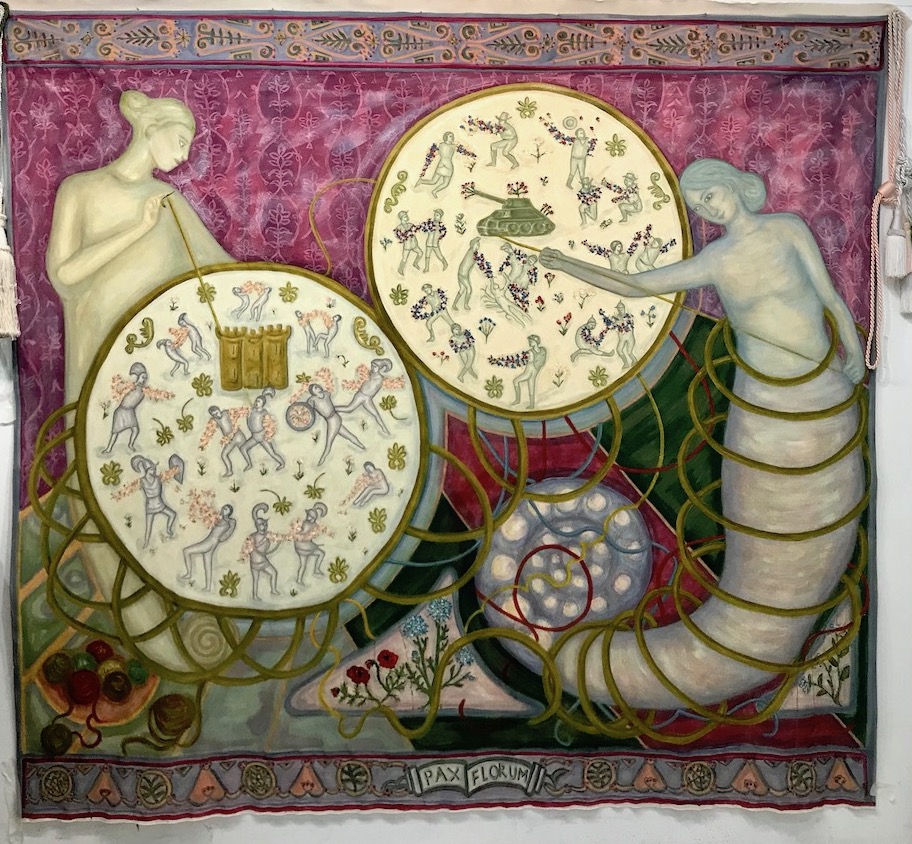

Not every story has to be a battle, acrylic, oil, wool on canvas, 200x180cm

This painting started simply with curiosity about a tapestry reputed to be at Wartburg Castle that has a medieval scene in front of a castle that has soldiers with flowers arms (referenced in A short history of tapestry by Eugene muntz p. 109).This description fired my imagination: what would war look like if all violent ‘arms’, (weapons and human arms) were turned into flowers?

Historical tapestries served many differing purposes, they were no mere decoration; they were a symbol of power and luxury, often won and displayed as trophies from battles; propaganda celebrating heroic scenes, they displayed family insignias of power; they invisibly celebrated the talents of the women who made them; they were moveable insulation that kept the draughts out in the winter. They were woven texts that through allegory and symbolism employed parallels and allusions beyond a simple reading of the image of the story depicted.

The title quotes Ursula K le Guin who wrote extensively about story telling, refuting a typical requirement of every story for war and conflict and violence with the phrase:

‘not every story is a battle’. Her use of Elizabeth Fisher’s ‘The carrier bag theory of human evolution’ (Women’s creation McGraw-Hill, 1975) focuses on an alternative reading of human evolution as essentially a peaceful process, that we are ‘gatherers not hunters’. Fisher proposes that the first cultural device or invention was probably not an axe or weapon, it would have been some kind of recipient, a pouch, a bag, a sling, a sack, a medicine bundle, something to hold gathered products. Thinking of humans as essentially peaceful, instead of uniquely violent, changes assumptions about the inevitability of war and conflict. It changes the stories we tell ourselves about human nature and offers hope

The painting also mocks ‘heroic’ male posturing and it gives value to ‘women’s work’, especially in relation to war. It makes reference to peace banners with its border featuring the words Pax florum (peace flowers). One working title was ‘Lay down your arms’ in commemoration of Baroness Bertha von Suttner, whose eponymous 1889 book helped initiate women’s peace moments in the 20th century that included Jane Adams’ International congress of women, and the Women’s International League for peace and Freedom (WILPF). ‘Flower power’ (a phrase coined in 1965 about how to use flowers as a symbol of peace and refusal to fight), poppies, cornflowers, lilies, flowers for Remembrance all feature in the a painting as reminders of the their powerful symbolism for anti-war statements.

Women’s transformative roles in living and dealing with war, male violence and the resulting hubris has historically found women collecting and telling different stories about war.[1] The main figures in the painting are working on giant embroidery hoops that echo arenas of war (or perhaps circus rings?) The historical role of women in the hugely significant production of cloth and weaving, from the Greeks to the Industrial Revolution is a role that has been deeply devalued since the massive overproduction of cloth by mechanical means. It is hugely ironic that it was women’s labour that enabled men to create wars (i.e. producing battle fodder[2]), and enforced war historical propaganda via domestic crafts like embroidery and weaving (eg the Bayeux Tapestry).

The embroiderers in the painting mock heroic versions and glorifications of war by replacing all arms with flowers. Part human part animal, the figure on the left is a powerful transformative figure, who conjures our connections to nature and peaceful gathering roles. [3] The small figures within the circular ‘hoops’ gesture in stereotypical ways, inspired by the idea of Warburg’s ‘pathos-formel’ theory. The gestures, movements and expressions of figures within visual stories engage our sympathies (pathos). Here such ‘pathos’ is subverted into a comedic non-violent dance.

Threading elements together, the use of connective lines and gold bands (shaped like a cornucopia, a symbol of peace) weave and create a sense of complicated and interconnected networks, symbolising our human connection and reliance on each other. Employing many effects and motifs that are repeated, combined, and overlapped, this ‘peace banner’ aims to contradict the assumption that war is inevitable and instead offer stories that show our will to peace. We are not blind to the challenges but in confronting the deeper roots of conflict and believing sustainable peace is in our nature gives us a glimmer of hope.

[1] A great example is Svetlana Alexievich’s book Last Witnesses: Unchildlike stories, providing first hand accounts of the human consequences of war on women and children via collected stories from adults that had survived as children during the Second World War.

[2] Lysistrata, a Greek/Roman play about Roman women refusing to have sex and children until men stopped fighting and killing

[3] The painting links to ‘gatherers not hunters’ and Delpha’s ‘Bag Theory’ project

Shown at Longya curated by Matt Retallick at Tremenheere Gallery & Falmouth Painting Platform, 2025

About this painting:

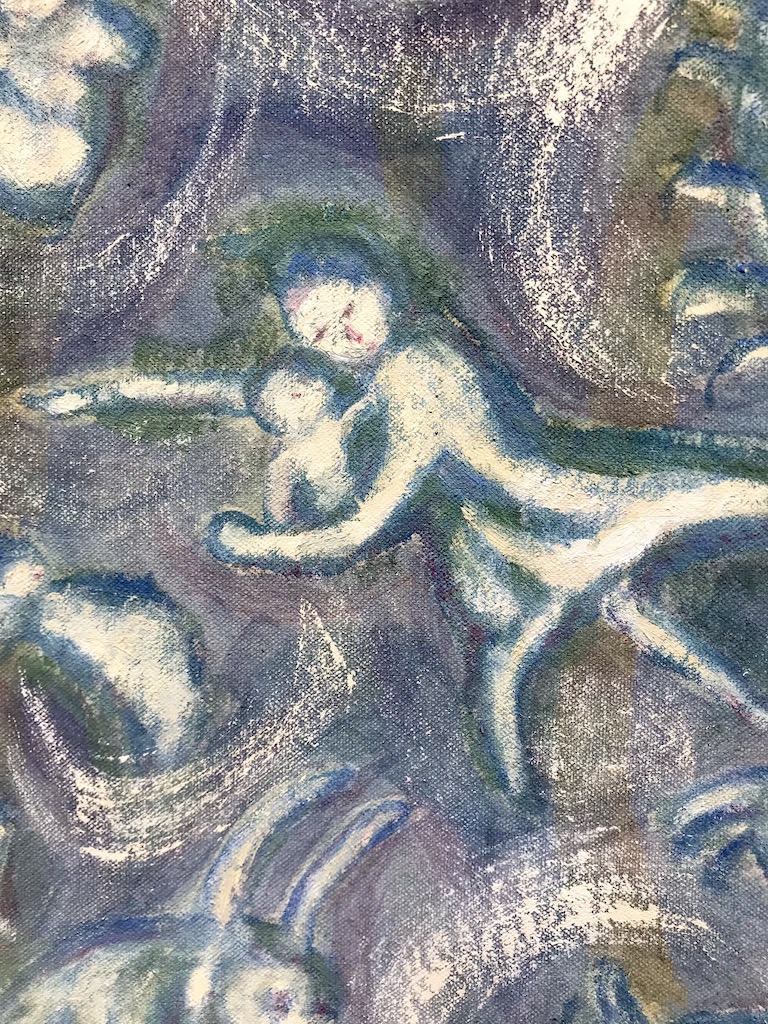

The title is taken from a phrase in Susan Griffin’s book ‘Made from this earth’.Griffin’s writing is a stream of consciousness, a multi-vocal meditation, a struggle to find a language within nature and organic life that is not controlled by patriarchy. The painting is an imaginative psycho-geographical meandering from Cornish granite walls, its old churches with their carvings, mythologies and misericords, to tales from ancient Greece. Connecting histories and places that are sites of conflict and resolution between nature and man.

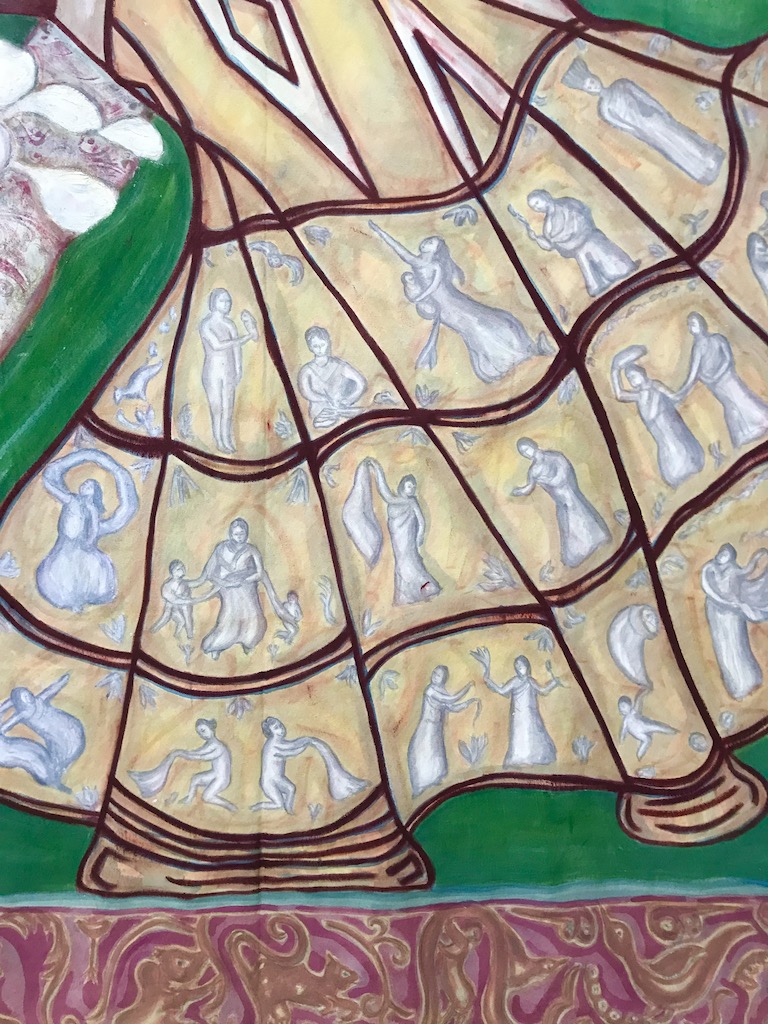

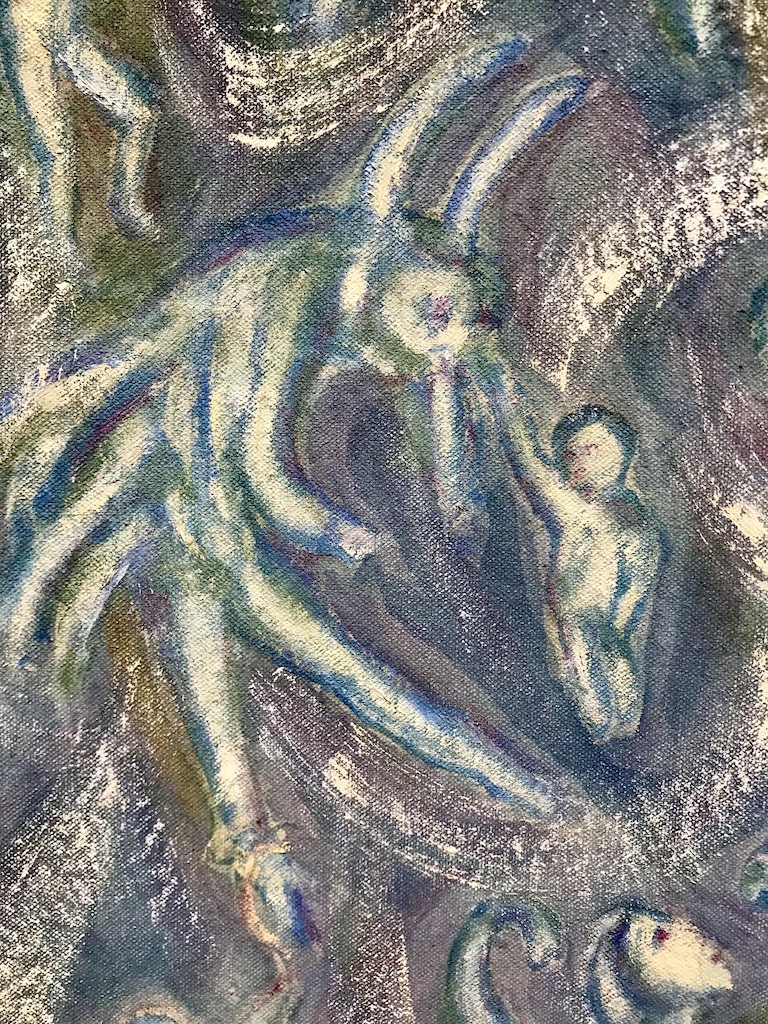

The mythical and implausible fabulation of a worm-like creature whose sinous irrepressible energy celebrates the female, the monster ‘goddess’ who for a substantial period of human history was respected before being co-opted by men. In ancient societies women had primary roles and goddess worship reflected this, Athena the goddess of wisdom originally honoured essential caring and domestic roles including weaving but over time she was named the goddess of war, ousted and appropriated with a shift to male military power in which women along with children animals and land resources became the prizes in raid and conquest. Greek mythology, like so many societal structures revel in the glorification of war. Understanding and re-imaging with these myths shifts us back to a different mode, way of understanding patriarchal power and control and perhaps mitigating what has become culturally acceptable.

Mythologically an ambiguous ‘she’, ‘a bane to many men’ (as described by Homer in the Illiad) there is a fascination with the female body and the monstrous Other. In this painting she wears a fantastical yellow skirt or ‘poplos’. Every fourth year in August the Greeks celebrated the goddess Athena with a Panathenaeaic festival in competition with the more famous Olympic games. Amidst music, rites and epic poems a new embroidered robe was presented to Athena. A symbol of the fabric of society, it was raised to the wind to sail forth, in a resolution of discord into harmony. The golden ripeness of her skirt contains figures that replace triumphant battle scenes with celebratory images of women’s lives. Many are references to peaceful scenes from the Parthenon frieze (acropolis Athens c460), including a figure of a pensive Athena posed similarly to the famous sculpture of the male ‘thinker’. The stories contained within the skirt, speak of a different knowledge, a different grace from the qualities admired in a male-centred world.

Connecting goddess symbology to other ancient local traditions in Cornwall that feature a corn goddess and the infamous figgy dowdy goddess (from dowes) goddess of deep water, the sky is full of cryptids, mythical beasts and choughs, the Cornish bird symbolic of resurrection and conservation, they are also unpredictable fluid inchoate forms above some curious figures behind a Cornish granite wall. The role of these colourful and bizarre figures in relation to the central figure is intended to invite multiple readings and questions. It is not clear if they are hunting or harassing or celebrating. There is no correct answer and although this writing outlines some details about sources and referents, painting is not necessarily a prescriptive endeavour it invites imagination and multiple readings.

The border is loosely based on drawings from ancient Cornish churches with the appropriate link to misericords in which Misericorda from the latin means pity or mercy, these carvings often fold up to form a ledge to make comfortable standing during long services of worship, it has been noted that they often look like woman’s reproductive organs.

Merging multiple stories and fantasy, voicing deeply felt contradictions about place and women, the painting is a ‘binding song’ that craves connection between contemporary and historical myths and aims to undermine reductive and didactic narratives about women and their relationship with nature, place and society. Playing with tropes and re-imagining and re-imaging new ones, the ‘many faceted drama of creation and renewal, remembering and forgetting, interaction and transference of cultural exchange’ is a call for continuous change and continued struggle. The furies are still calling patriarchy out.

Delpha Hudson, March 2025

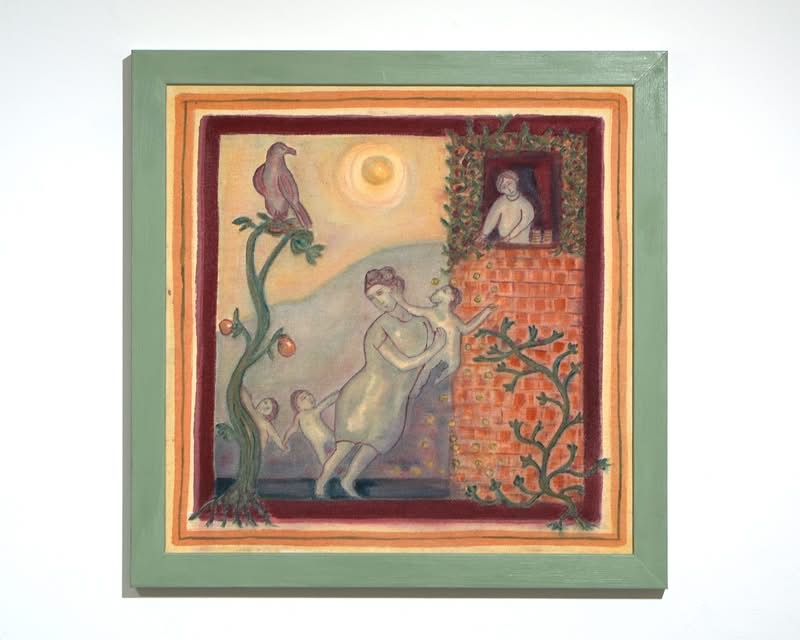

About this painting:

Painted to explore the maternal body juxtaposed with contrived human landscapes, the title The lie of the land hints at how the patriarchal control of both reproduction and nature distorts cultural views about women, landscape and motherhood.

Look carefully and medieval tapestry-like figures and motifs are woven together within intersecting planes that explore the lie about equality. Women are still doing the bulk of unpaid care and domestic work, or low paid jobs. Patterns create a palimpsest of time showing women working, caring, supporting; a rural ‘toile de jouy’ filled with humorous pastoral figures and scenes of women and children, farm animals, and even a donkey; an ancient Coptic pattern with weird hybrid creatures and women and children; a 70s pattern with womb-like shapes that contain not babies but women; borders of brightly coloured modern grotesques. Trees grow right through the painting. The main figure with a rucksack on her back is bent double holding a tiny baby very carefully in a tender gesture of care.

Just as ‘Cornwall was made by nature, then remade by miners’ representation of the mother’s body have been ‘remade’. Just as ecofeminism finds that women’s body as ‘closer to nature’ echoes the control of nature and landscapes by power structures created by men, this painting also references the lie about ‘wild Cornwall’. Appropriated and sold the ‘wildness’ of the Cornish landscape is promoted, commercialised and controlled, and the gentrification and monetisation of place does not benefit the majority of people who live there, many of them live in poverty and have to accept badly paid jobs to survive, never being able to afford to explore the landscapes they live in.

The mining or tourist elements of the painting did not appear during the painting process. The tiny baby was a late addition too and became an additional metaphor for care and responsibility. Perhaps also personal as I still often have recurring dreams of small babies that are not my own but for whom I am somehow responsible. Left in my care, these are disturbing, anxious dreams. I must make sure they are cared for.

Delpha Hudson, January 2025

Telling Tales exhibition with ceramicist Debbie Prosser at Penwith Gallery, St Ives, January 2025

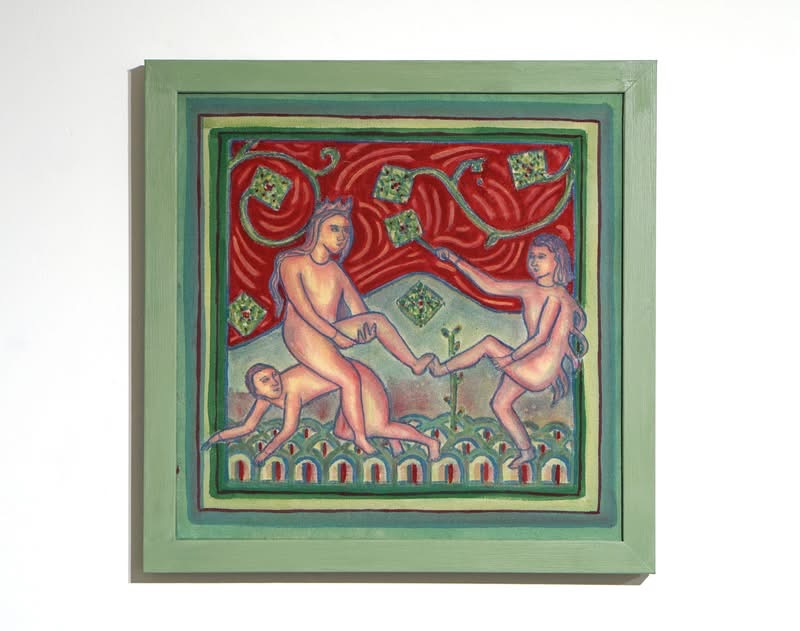

Paintings and ceramics that use a vernacular of colours, symbols and patterns with multiple and entangled narratives. Assimilating mythologies from the past and realising them in a visual language of the present explores our stories and what we value.

Narratives are microcosms of collective renewal. We are at once in the middle of the tale with yet unwritten future endings. Stories and tales are compasses, we navigate by them, and from them we build an understanding of our lives and the world around us.

In Telling Tales, Deborah Prosser and Delpha Hudson use figurative medieval and classical imagery borrowed from many sources to create a historical-contemporary visual lens to explore women’s lives. They create visual stories in an endlessly inventive way that honours, acknowledges and connects us to the invisible work of women.

Both artists mediate between different worlds and multiple time frames, including a medieval vernacular with multivalent references that garner a relationship with the past. Rich with ancient and innovative imagery, flora, fauna and pattern, the surfaces of ceramics and paintings examine, explore, and reframe the present.

Visual story telling has the potential to twist the fabric of our reality and disclose the fruitful premise that women are the holders of stories and their tales are a significant source of empathy for others and the places we live.

Telling Tales exhibition installation of paintings and ceramics by Debbie Prosser at Penwith Gallery, St Ives, 2025

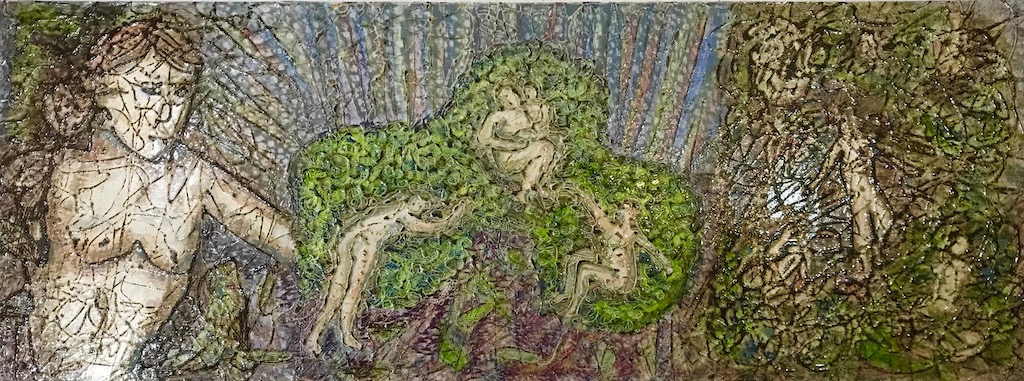

Painting with bitumen & oil 2025

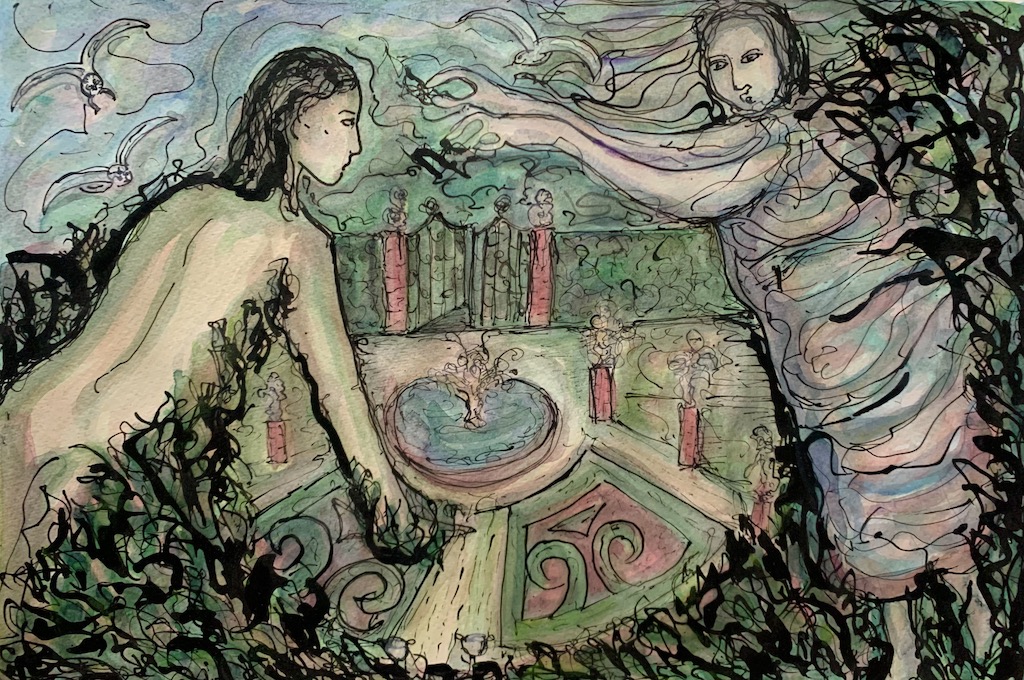

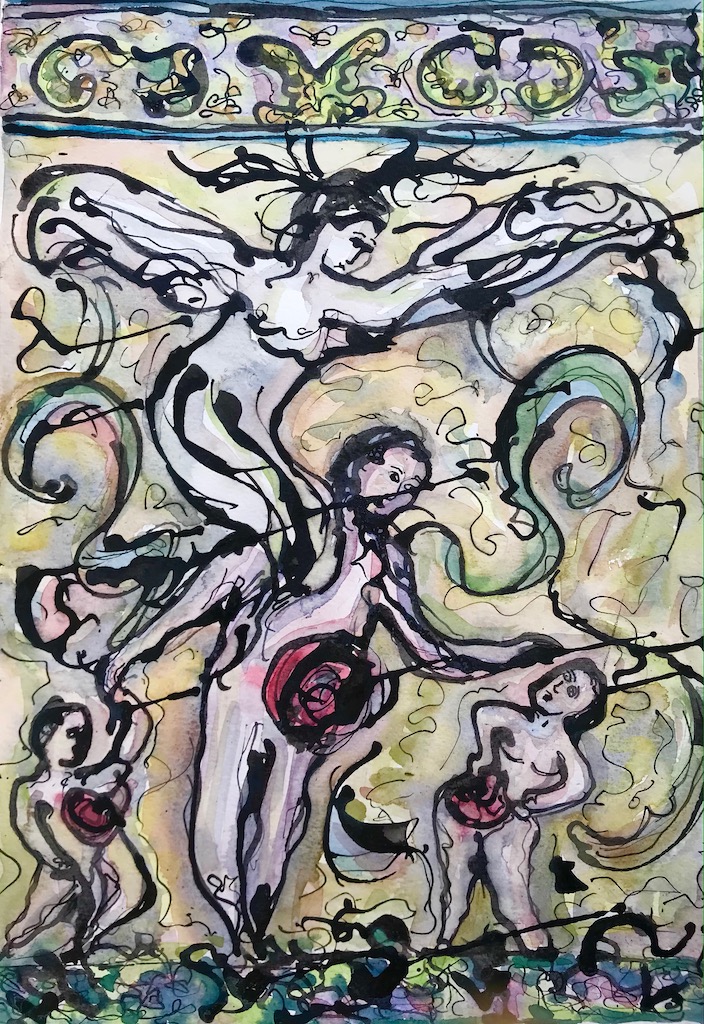

Ink & watercolour on paper

For more news about latest projects and paintings follow Delpha on Instagram